Our latest news and analysis.

Valuation Multiples And Their Significance In Business Sales

In any business sale transaction, valuation is always a key consideration. Central to understanding company valuation is having a firm grasp of the concept of a valuation multiple, which is an extremely common valuation tool, particularly for private companies.

A valuation multiple is simply a ratio that expresses the value of a company as a function of a specific performance metric.

Company Value = Multiple (X’s)

Performance Metric

Performance Metric

As an example, if a company is valued at $10.0m and the relevant performance metric, say, net profit after tax (“NPAT”) is $2.5m, then the corresponding valuation multiple is 4.0-times net profit after tax.

$10.0m = 4.0 (X’s)

$2.5m

$2.5m

Another way of viewing this multiple is to say that if the company is being valued at 4.0-times its net profit after tax of $2.5m, then it is worth $10.0m.

Valuation Multiples & Different Time Frames

A multiple can be either forward or backward looking depending on the time period of the underlying performance metric being considered. Common time periods that are used in multiples analysis are last financial year, trailing twelve months and next financial year.

Picking up on the example above, let’s assume that the company continues to be valued at $10.0m. However, let’s also recognise that the company’s NPAT amount will vary depending on over which time period the NPAT relates as is shown below:

| Last Financial Year | Trailing Twelve Months | Next Financial Year | |

| Value | $10.0m | $10.0m | $10.0m |

| NPAT | $2.5m | $3.0m | $3.5m |

| Multiple | 4.0 (X’s) | 3.3 (X’s) | 2.9 (X’s) |

As we can see, the company is being valued at 4.0-times its historical NPAT (ie. the NPAT from the previous financial year), 3.3-times its trailing twelve months NPAT and at only 2.9-times forward NPAT (ie. the NPAT being forecast for the next financial year).

This gradual decline in multiples is to be expected because most companies tend to assume growth into their forecasts. Either way, it is very important to be clear in terms of which time period the denominator of any multiple is referring to.

In our experience, when a purchaser expresses a willingness to purchase a company at, say, 4.0-times earnings, they are far more likely to be applying that multiple to historical earnings (last financial year or the trailing twelve months) than they are to forecast earnings.

Key Performance Metrics

A valuation multiple can analyse the value of a company against at least four different types of performance metrics. These broad metrics are as follows:

Revenue:

– Company Value / Revenue

Earnings:

– Company Value / EBITDA (Earnings before interest, tax, depreciation & amortisation)

– Company Value / EBITA (Earnings before interest, tax & amortisation)

– Company Value / EBIT (Earnings before interest & tax)

– Company Value / Free Cash Flow

– Company Value / NPAT

– Company Value / EBITA (Earnings before interest, tax & amortisation)

– Company Value / EBIT (Earnings before interest & tax)

– Company Value / Free Cash Flow

– Company Value / NPAT

Assets:

– Company Value / Book Value of Assets

Industry Specific Variables:

– Company Value / KwH or Subscribers etc.

These different categories of metrics have different strengths and weaknesses and different circumstances for when they are more or less appropriate to use for valuation purposes.

For example, in early-stage, high-growth companies it is common to use a revenue multiple when assessing value. That is because such companies are often loss-making, which would make using a valuation multiple based on earnings meaningless.

Alternatively, for more mature companies that are earnings-positive it is more common to use an earnings-based valuation multiple because ultimately that is why companies are in business – to earn a profit.

One of the key reasons why EBITDA is commonly used as the denominator in valuation multiples is because it allows for greater comparability between firms. EBITDA removes the impact, for example, of depreciation, which can be affected by different accounting treatments between companies.

In addition, EBITDA is not affected by a company’s capital structure or tax position. By removing these elements, it is often argued that EBITDA gives a clearer insight into companies’ underlying business performance.

However, it can be argued that if, say, capital expenditure is an important part of a business, removing depreciation from a key performance metric may result in ignoring a key dynamic of the business. In these circumstances, perhaps, EBITA would be a superior metric.

Some industries also commonly use variations of EBITDA in valuation multiples because those variations are the standard basis for assessing operating performance in that industry. For example, in the oil and gas industry, EBITDAX (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, depletion, amortisation and exploration expenses) is commonly used in valuation multiples.

Non-financial, industry-specific metrics can also be useful for making comparisons between firms within a given industry. It is common in the digital streaming industry (companies such as Netflix) to use the number of active as a key performance metric within multiples.

The key point is that a prospective seller of a business needs to know the standard valuation multiplies that are used within their industry and to have the relevant key performance metrics to hand.

Enterprise Value vs. Equity Value

Another important consideration with multiples is to ensure consistency between the numerator and the denominator of the ratio. If the company is being valued on an enterprise value basis, then the performance metric in the denominator needs to relate to EV.

Alternatively, if the company is being valued on an equity value basis, then the performance metric in the denominator needs to relate only to equity value.

Essentially, EV values the company as a whole whereas equity value measures the value that is only available to the company’s shareholders. For a detailed overview of the distinction between enterprise value and equity value, please click here.

The key point is that any performance metric that is calculated before the deduction of interest is an enterprise value multiple because it captures the value available to all claimants over the company – ie. the holders of both debt and equity.

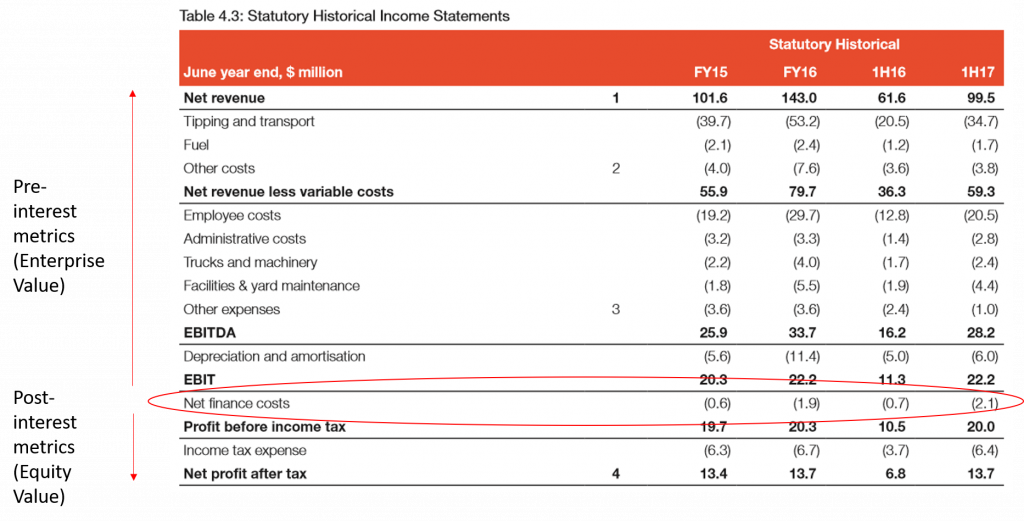

The value that remains after the deduction of interest is only available to equity holders because once interest has been paid, debt holders have no further claim over the company. This is demonstrated in the following screen grab from the prospectus for Bingo Industries, the waste management company.

What this demonstrates is that metrics such as revenue, EBITDA and EBIT are pre-interest and, therefore, the amounts available at each of these lines of the profit & loss statement are available to both debt and equity holders. However, NPAT as an example is only available to equity holders.

Valuation multiples are a key concept in corporate finance and are particularly important in the context of a business sale transaction. If you would like to have a confidential discussion about how CFSG can assist you in successfully preparing for and completing the sale of your business, please contact us.