Our latest news and analysis.

Cash-Free-Debt-Free

When a company receives an acquisition offer, it is common for the proposal to value the business on a “cash-free-debt-free” (“CFDF”) basis. For example, the letter of offer might state the business is being valued at, say, X-times the previous 12 months’ EBITDA on a CFDF basis. It is essential that business owners understand exactly what CFDF means because it can have a significant impact on the actual proceeds they walk away with from a transaction.

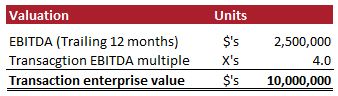

Let’s look at a simple example: a business that is being valued at four-times its trailing 12-month EBITDA of $2.5m. That yields a transaction enterprise value for the business of $10.0m as shown below. This is commonly referred to as the headline price.

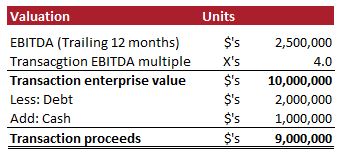

While the business is being valued at $10.0m, that does not mean that the sellers will necessarily receive that amount of money in their pockets. Why? Because the business is being valued on a CFDF basis. That means that prior to completion, the sellers will be responsible for paying out all of the business’ financial liabilities. They will also be entitled to retain whatever excess cash there is in the business. This cash is typically extracted via a dividend prior to completion.

Extending the above example further, let’s assume that the business has $1.0m of cash on its balance sheet and is carrying bank debt of $2.0m. The total proceeds that the owners would receive, all things being equal, is $9.0m as shown below. These and other adjustments are commonly referred to as the enterprise value to equity value bridge.

Clearly, selling the business on a CFDF basis has a material impact on the total proceeds that the vendors ultimately receive.

Working Capital

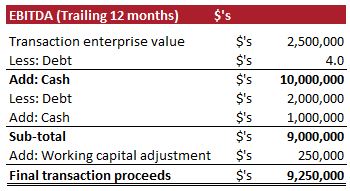

As a brief side note, it is worth mentioning that in addition to CFDF considerations, another common area for completion adjustments in a transaction relates to working capital (“WC”). WC refers to a business’ short-term sources and uses of funds – typically debtors, inventory and creditors. Prior to completion, the parties to a transaction will agree on a “target” level of working capital with any surplus or shortfall requiring an adjustment to be made.

So, looking at the above example again, let’s say that the parties agree that at completion the business must have working capital in the business of $0.75m. That is the working capital target. Let’s assume, however, that just prior to completion, the business makes a large sale that boosts working capital to $1.0m. That is $0.25m over the agreed target and as a result, an adjustment as shown below will be required.

The objective is fairness: an acquirer purchasing a business as a going concern wants to ensure that the business has sufficient short-term funds available to continue operations without having to immediately reinvest its own additional funds into the business. Equally, a vendor does not want to “gift” the purchaser a large injection of future funds because, as shown above, an unusually large debtor pays for past goods sold.

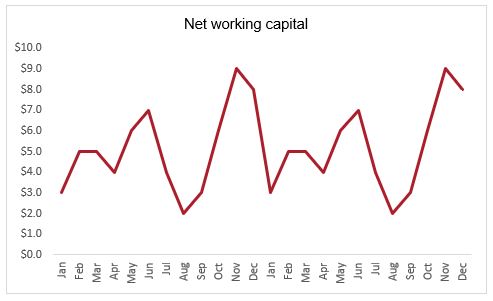

Arriving at the target level of net working capital requires careful analysis of historical and seasonal trends and is often an important part of any M&A negotiation.

Definitions, definitions

Returning to CFDF considerations, the earlier discussion arguably oversimplifies the issues associated with CFDF transactions. While certain items clearly meet or do not meet the respective definitions of cash or debt, many fall into a grey area. These are commonly referred to as debt-like or cash-like items and can often be a source of much debate and intense negotiation during the sale process.

For example, a bank loan that was taken out to fund the purchase of a new piece of equipment would likely meet any reasonable definition of debt. How about, however, a business with a large deferred revenue balance – cash received in the past for future work that needs to be provided in the future? Do those future obligation – that will be undertaken by the purchaser – effectively constitute debt that should be borne by the seller?

Looking at cash-like items, there are many instances where cash sitting on the balance sheet could not be readily extracted by the seller without negatively affecting the business. For example, a security deposit on a leased property could not be extracted assuming the business intended to retain occupancy of the leased premises post transaction. Similarly, cash held on behalf of a customer may also be deemed as “trapped” cash.

When it comes to these “grey” examples of debt-like and cash-like items, there is no roundly agreed definition. Inevitably, the final view will be based on the specifics of the business and the overall flow of the negotiations. Either way, a key aspect of preparing a business for sale is conducting an analysis of a business’ balance sheet and forming a considered view on what items may or may not become part of the CFDF discussion.

If you would like to have a strictly confidential discussion about how CFSG can assist you in preparing for and successfully completing the sale of your business, please contact us.